Seravezza Fotografia confirms also this year confirms its guidelines by presenting a full program of events of great interest and quality: the first photo exhibition by Frank Horvat titled " House with Fifteen Keys " held at the Palazzo Mediceo in Seravezza Fotografia 2014. The event is basically a retrospective that chronicles 70 years of photographic work of the great master who was born in 1928 in Italy in Abbazia , today a Croatian town known with the name of Opatija. Photos of reportage, fashion, portrait, landscape and street photography are expertly collected and reconsidered by the author in an exhibition of 290 photographs divided into 15 keys of interpretation. This collection also offers some extrapolations from personal photo projects made from the 80s to today.

The exceptional photographic work to date made by Frank Horvat and the importance of titles given to the "15 keys" such as "light", "Human Condition", "Voyeur" confirm Frank Horvat as one of the most important contemporary photographers who can afford to say that photography is the art of not pressing the button.

“photography is the art of not pushing the button”

Why keys?

I am at the age when one looks back and tries to make sense of it all.

I had the luck to take photographs for almost 70 years, in a period when the

world changed more than in any comparable time span.

To live in 6 different countries and to travel to several more.

To think, speak and write in 4 languages.

To photograph many subjects, from different viewpoints and with different

techniques.

To have other interests beside photography, such as writing and olive growing.

My eclecticism had it's drawbacks. Some questioned my sincerity. Some found

that my photos were hard to recognize, "as if they were by 15 different authors".

This is why I went through my work (or through what has been preserved of it),

searching for a common denominator.

I didn't find one - but 15. Running (more or less) through all those years.

I called them keys.

Frank Horvat

House with 15 keys:

Light

The human condition

Time suspended

Voyeur

Eye to eye

Metaphors

Makes you think of...

Two

Many

The ‘real’ woman

Doesn’t quite fit

Things

'Dumb' photos

Self-portraits

Light

2003, Cotignac (France), Grègoire's Hands

Everyone knows that photography means ‘writing with light’. As Niepce, Daguerre and Talbot began doing around 1830, and as a billion people do now with their mobile phones.

What is a little different - in my case and in that of some others - is that I react almost more

to the light itself than to the objects on which it shines. To the point that I seldom use a flash, i.e. a light that can be seen only after the shot is taken. And that I wouldn't press the shutter even in front of the most interesting person (or event), unless I felt that the way it’s lit is significant.

This comes from the obvious fact that photography, beside being about light, is essentially about time (or rather about the stopping of time). Which in turn is why the instant is decisive, in Cartier-Bresson's famous words.

Light, to me, seems all the more decisive as it’s fleeting (just as time itself). Which is why I am less interested in that of a landscape at noon, under a blazing sun, than in the light at dusk, or under a moving foliage, or in some interior, with highlights and shadows changing continually, depending my own movements and on what goes on around me.

And also why (to me) the forerunners of photography were not so much the painters of the Quattrocento, with their perspective and their camera obscura, nor Caravaggio with his violent light effects, as the 22 years old Rembrandt, in his self-portrait now at the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, where most of his face is hidden by a seemingly accidental shadow, except for his right cheek and the tip of his nose. As if to say: these parts have to stand for the whole.

1950, Polesine (Italy), Paesants, replacing their oxen, lost in a flood

I've been asked: ‘what do you mean by ‘the human condition’?

The best answer I can give is that ‘human conditions’ means having problems. And that to me, those who have problems seem more interesting than those who don't.

Artists have been aware of this for a long time - particularly western artists. Photographers didn't take long to follow.

Many photographed poverty, disease and war. Several produced great images, and became famous. A few felt guilty about their succes - as if it had been at the expense of the suffering - and justified themselves by claiming their intention to alert public opinion, in order to prevent future suffering. I tend to be skeptical about these claims - even if I trust their sincerity and admire their courage.

As for myself, I never photographed war - possibly because I lacked the physical courage. But even in peacetime I wouldn't direct my camera at a relative (or a friend) finding himself in a painful situation. Simply because it wouldn’t seem right to take advantage of his misery for my own photographic ends.

Admittedly, I haven't always been so considerate with strangers. Partly because I understand

magazine readers, wishing to ‘witness’ extreme and even tragic events. Just as I don’t blame passers-by, neglecting their business and crowding around the victim of some traffic accident. After all, it is their business, that same misfortune could have happened to any one of them. Watching it can be seen as an act of sympathy (or of compassion), in the original sense of these words: sharing the plight (pathos, passio) of a fellow human being.

It is true that for a photographer the borderline between excessive intrusiveness and excessive aloofness can be narrow. All I can say is that I did my best, by trying to suggest problems rather than pointing to them.

1962, Cairo, swinging girl

Any photograph, of course, is a suspension of time - but some are more of a suspension than others. Or, reciprocally: the camera can suspend any moment of time - but some seem more worth suspending than others.

As Faust says to Mephisto, when waging his bet:

If ever to the moment I will say:

"Ah, linger on, thou art so fair!"

Then may you fetters on me lay,

Then shall I perish, then and there!

Then may the death-bell toll, recalling

Then from your service you are free;

The clock may stop, the pointer falling,

And time itself be past for me!

There is indeed something faustian (or mephistophelic), about this tool - allowing us to freeze the flow by which we are carried. Except that at the end of Goethe's tale, Faust is redeemed, time is restored and Mephisto's gifts turn out to be nothing but make-believe.

Something similar could be said about photography: did I really - when pressing the shutter - believe that those moments were worth preserving? Do you really - you the spectator - feel that the flow has been suspended?

I am not sure about how to answer the first question: so many years have passed, so many times have I reconsidered and reprinted these pictures! As for the second, the answer is up to you.

1952, Lahore (pakistan), Hira Mandi, young dancer

Voyeur is a french word for someone seeking sexual satisfaction through his eyes - rather than ‘normally’, through more suitable organs. But also, in a wider sense, for someone keen to penetrate, or to grab, or to possess through his sight, though not necessarily with a sexual intent.

In this sense, all photographers are voyeurs. I don't mind being included in the lot and acknowledging voyeurism as one of the keys to my house.

Except that when I selected the photographs for this chapter, the ones that seemed to fit were not so much associated to sex, as to a slight feeling of guilt, which I either remembered (when I could recall the circumstances of the shoot), or that resurfaced while looking at the contacts.

More like a short sting than like a lasting remorse for ‘having exploited other people's weaknesses’. And mainly because voyeurism is such a one-sided affair, in which one ignores the other party's inclinations (or disinclinations).

Would this world-famous fashion designer have liked to see himself in that feminine attitude? Or this fond Bengali father, to realise the fright of his little daughter (if indeed she was his daughter) resisting his embrace as if she feared being raped? Or this lady on Madison Avenue, who may have spent hours in front of her mirror, trying to restore the look of her youth, if she had seen her mask as it appeared in my viewfinder?

Not that I spend many sleepless nights pondering about these hypothetical reactions. But

voyeurism - like other obsessional pursuits - has its backlashes of remorse.

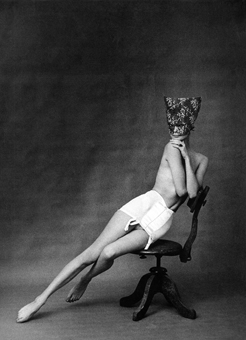

1958, Paris, advertisement for lingerie

When a person looks at my camera, I refrain from shooting - contrary to the widespread

belief about the eyes being a door to the soul (or something of the kind).

In the beginning, this came from Cartier-Bresson and his ideal of the invisible (or at least inobtrusive) photographer. The theory was to show das Ding an sich (the thing by itself), as Kant might have said. Of course this was a fiction and was to became just another convention, which William Klein broke by including, in some of his New York street scenes, one or two people looking straight at the lens - and demonstrating that their reaction to the photographer made the image look all the more believable.

Nevertheless I stuck to the theory, probably because it suited my temperament. Especially

when I got into fashion photography and found that the models’ passionate stare at the camera, far from being a door to their souls, was just the easiest and laziest of their routines.

On the other hand, I always knew that there were times when someone - out of surprise, or of fear, or of anger, or even of love - would suddenly look up at me. At me, not at my camera. And that if I succeeded in catching that moment, I could get a shot worth getting.

As with this close-up of Mate (pronounced Mah-tey).

It wasn't one of our best days. We had quarreled, as often. But I had to do a test with a new lens, and she agreed to pose. While still upset, and still looking at me with a mix of anger,

pain and affection.

Eventually we separated, and didn't see much of each other for years. At the end of her life, I visited her in hospital. Our son Marco had placed that print on one of the walls, so that the doctors and nurses could see what kind of a person their patient had been.

Still, images like this one are exceptions. Most of the time, I avoid photographing people who look at me. Because I believe that their attention to something else (or even a view of their profile or their back) can reveal a lot more about them. But then exceptions, as the saying goes, are the best proofs of a rule.

1953, New Delhi, Jantar Mantar, ancient astronomical device

A metaphor is an idea which stands for another idea - or for several, depending on how it is meant and understood.

A symbol is almost the same, but not quite. The turtle, for instance, is a symbol for slow motion, as in the famous paradox of its race against Achilles and in countless allegories, emblems, ads and icons. But the three turtles in my photograph are metaphors.

Metaphors for what? I won't tell you. By telling, I would spoil the game and deprive you of the pleasure of guessing. All I can say is that I have several answers in mind, and that I hope you will find others that I didn't think of. Even if they are far-fetched, or if they exclude each other.

Metaphors are what poetry is made of . ‘Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player, that struts and frets his hour upon the stage, and then is heard no more; it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.’ All the substance of Macbeth is in these lines.

But metaphors are also the substance of advertising, poetry's mercenary child. And of photography, which - at least as I practice it and contrary to a widespread and mistaken belief - is only a distant cousin to painting, and more like a kind of schizophrenic offspring of poetry and technique.

1984, Paris, Claude

In 1981, while following the trail of Goethe's sicilian journey, I drove through Monreale,

a small town where the illustrious traveller stopped to visit a curate who shared his interest

in geology and whose specimens Goethe describes at great length. What he doesn't mention (and what I therefore ignored), is that this town is famous for its byzantine basilica, almost as

impressive as San Marco in Venice, but irrilevant to a man of the Enlightement, to whom

the 1200 years between the Roman Empire and the Renaissance were nothing but an interval

of darkness.

A present-day Goethe wouldn't have such a blind spot, or would at least have googled up

Monreale before landing at Palermo Airport. Except that such a person is hard to imagine.

Since the 18th century, knowledge and the instruments for acquiring it have been immensely

extended, but something else has been lost.

I'm not complaining. After all, the extension of our knowledge allows me to see what was hidden to one of the greatest geniuses of all times, even though my vision, as a result of that

loss, has become a bit blurry.

This combination of progress and regression may be a way to describe culture in the age of

post-modernism. Nowadays, on our computer screens, all the separate and different approaches to art, from the Stone Age to Dokumenta, seem contemporary and comparable.

All can be downloaded and exploited for comment, quotation or association - within the

(all too narrow) limits of our curiosity, our awareness and our attention span.

All this comes to my mind when I try to explain what I mean by makes you think of...

Which of course is just one of my keys. In most cases, my first reason for pressing the

shutter is the light I see falling on a subject. Then, almost as an afterthought, come the

ideas, the feelings, the memories and the expectations - conscious or unconscious - that

I associate to what I see. Though my imaginary museum, as Malraux called it, is only a

fraction of that stock.

1959, Paris, Monique Dutto at métro exit

One goes with the first person singular.

One is like alone, apart, solitary, separated, unique.

Like the stranger in the crowd, the lonely wolf, the last cigarette,

the tree on top of the hill, the coq in the henhouse, the captain

on the sinking ship, the first love.

Like my nose, my mouth, my heart, my belly button, et coetera.

Like the Earth, the Sun, the Moon, the Universe. Like Jehova

(or Allah, if you prefer). Like the ace of spades.

Like my mother, like my father, like me.

2008, Venezia (Italy), illustration to the erotic poems of Giorgio Baffo

Two goes with the second person singular.

Two are your eyes, your ears, your breasts, your buttocks,

your hands and your feet.

Two are husband and wife, master and dog, day and night,

good and evil, Republicans and Democrats, yin and yang.

Two is what you need for dialogue, chess, equality,

similarity, difference, contrast, competition, friendship, war

- and of course for love: in order to say ‘two’ you have to

acknowledge the other, and whatever goes on between

you and the other.

1956, Paris, at the Sphynx

Many goes with the third person plural.

I must admit that I have problems with that person.

In school, they used to taunt me.

They. The others. The crowd. The people. The masses: asses.

Photographing them, for me, may have seemed a way to

get the upper hand: ‘I am the one who is pressing the shutter.’

But then, I wouldn't be an acceptable photographer, if I

couldn't bring up a warm feeling to them as individuals (or

at least to some).

1976,Paris (France), for Vogue France

Mind, this is not a key to my whole house. Only to a part of it, at a given period.

From my adolescence and through the first years of my adult life, the woman of my dreams

was the exact opposite to my mother (Dr. Freud wouldn't have been surprised). Which is to say slender, tall and not in the least intellectual.

So that getting into fashion photography was like entering a Promised Land, where all those

who presented themselves in front of my camera seemed to come from that mold.

Only they were loaded with scoriae. Some that I couldn't get rid of: such as the gowns, the suits, the overcoats, the hats and the various accessories they had to wear. Hardly to my taste - but after all I was paid to photograph them, and the girls to wear them.

Then there were the crutches they used (and misused) to improve what they had been given by nature. Such as lipstick, mascara, foundation, false eyelashes, nail polish and especially

wigs, which in those days where thought to be practical, because they replaced hairdressing. Some top models had dozens, which they carried to their sittings in special bags.

All that didn't fit my dreams. But even worse were their stereotypes: the ardent gaze,

the cheery smile, the dreamy look, the orgasmic half-opened mouth, the hysteric laugh, not

to forget the proud gait, the sexy hip, the sensuous throwing back of the head. They spoilt my

dream, making its objects less believable - and hence less lovable. So that in order to uncover the 'real' woman (or at least a trace of her), my fashion sittings became battles against windmills.

‘Wipe off that lipstick! Get rid of those false eye-lashes! Couldn't we try showing your own hair? For heaven’s sake stop smiling! And never look at the camera!’

They didn't like it. Neither the models, who had invested a lot of money in their wigs, nor the hairdressers and the make-up artists, whom I antagonised, nor the fashion editors, whom I made feel insecure.

But my photos got published, because ready-to-wear fashion needed a more realistic photography, and because the editors-in-chief knew it.

1962, Roma, for Herper's Bazar, Debora Dixon

What doesn't fit?

How did this young beauty get into that trunk? Why does the man on a chair turn his back to those three ghosts and to that tired warrior? What’s this embarrassed dandy waiting for, in the middle of those contemptuous gnomes?

Were they set up? And if not, how did they get there?

Reading the captions may provide some answers - but do you really need to know?

The main point is that everything doesn't always and necessarily fit. Possibly, this is what made me press the shutter at that instant. And that now intrigues you.

2006, Boulogne-Billancourt (France), mandarine peel

As Marc Riboud once said to me: "I prefer moving subjects, because photography is

mainly about capturing one instant rather than another, catching it when it's ripe,

freezing it at the right time. Like the right note in music, or the right balance in

architecture. The pleasure is all the greater when the challenge is tougher, for instance

when the elements to be assembled are more varied, more mobile or less predictable."

(From an interview in 1986, published in Entre-Vues, 1990)

I agree. It's when your subject is moving that you take the bull of photography by the horns. Or, as I sometimes put it more bluntly, to young people showing me their portfolios: if you only photograph what you have time to reconsider, you are copping out.

But then, some of my own photos seem to prove the opposite: these shoes in Milano, 63 years ago, where not running away from me (I don't remember that shooting, and only just rediscovered that image - but it looks as if I took the time to re-arrange them...).

Nevertheless the back-lighting (and also my knowledge of the way I use to work) makes me believe that it wasn't preconceived - but that the situation suddenly struck me, as when you recognize something you know from your experience, or from your dreams, or from your mental associations.

So it was, after all, a decisive moment. Not in the physical existence of those objects, but in the uninterrupted flow of my mind.

1950, Venezia (Italy), fashion show

The word 'dumb', for a photograph, may require some explaining - hence the inverted commas. But I would rather that you find out by yourself. If some of these ones make you smile, you are beginning to see what I mean and you may recognize a dumb photo when you meet it.

If I show them last, it's because I cherish them most. And if the term by which I call them sounds derogatory, it's like a French mother calling her baby ma petite crotte (‘my little shit’).

Take ‘1950, Venice’. The fashion show was no big deal, except for the palazzo, the gilded

stuccoes and the patrician names of the attending ladies. The model had nothing of a stunning

beauty, even if the gentleman on the sofa (probably the husband of one of the ladies) seems

more interested by her than by the dress she's wearing.

I was 22, shooting with a flash and doing my best to please the people who had hired me.

When I saw the frame on my contact sheets, I didn't think much of it and wouldn't have

kept the negative, had it not been for another shot, on the same film, that I liked. (That was how some photographs, in the age of analog, escaped the dust bin).

Then one day, while leafing through my files, I saw it with different eyes. What had seemed

banal became significant, conveying something I hadn't been aware of. Or had I conveyed it unwittingly? Was it the sequence of those five expressions - the model's and the four

spectators' - as they were lit up by the flash? But when I pressed the shutter they were in the dark!

This, in a nutshell, is the miracle of a dumb photo: there seems to be a meaning, but that

meaning couldn't have been intended by the photographer.

Édouard Boubat used to quote Borges (from I don't know which of his works): ‘A writer, who writes only what he thinks he is writing, cannot be a really great writer.’ Likewise, you don't go out to take a dumb photo: it comes as a gift, just as Saint-Augustine said about salvation.

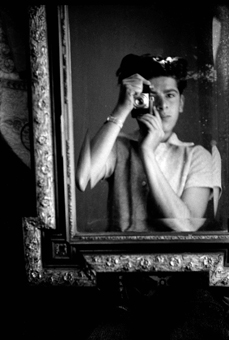

1945, Lugano (Swizzerland), self-portrait

Self-portraiture is as legitimate as masturbation, with the additional advantage of being

irreproachable.

Think of Dürer, Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, Rubens, Rembrandt, Velasquez, Chardin,

Goya, Delacroix, Van Gogh, Cézanne, Picasso, Francis Bacon.

And of course of Montaigne: ‘Wherein, finding myself totally unprovided and empty of

other matter, I presented myself to myself as argument and subject. It is the only book

of its kind, and of a wild and extravagant design.’

Curiously, I cannot think of many self-portraits by photographers (except the few who

made self-portraiture their trade-mark). Maybe because most photographers prefer to look at what's around them.

Even in my own case, I only discovered it late in life: the great thing about self-portraiture is having a model who is always available and compliant.

Most of the problems that come with it are technical: not seeing what you get (if you direct the lens at yourself), inverting right and left (if you shoot through a mirror), having the camera in your picture (in the same case), needing a third hand to release the shutter (if you photograph your own hands).

The greatest is that looking at yourself can get boring. Which is why this chapter is shorter than the others.

ORARIO: dal giovedì al sabato 15.00-19.00 e la domenica e festivi 10.00-19.00

Biglietto: intero 6.00 euro | ridotto 4.00 euro